"When I first came to New York City in 1962,

this was before the women's movement, when I went to a club, it was like

walking a gauntlet. It was just understood that if there was a woman on

the premises, the men were gonna hit on her. Now, this

is called sexual harassment. In those years it was considered to be

that's just how it is, you know? Like, what's there to think about? A

lot of women in those days were kicked off of bandstands and out of the

recording dates because of the prevailing notion, which was very strong

then, that men were better, that women were not as good as men. If you

thought that way, it was considered hip. This sexual harassment was very

intense." - Pianist Connie Crothers to the author, 2013

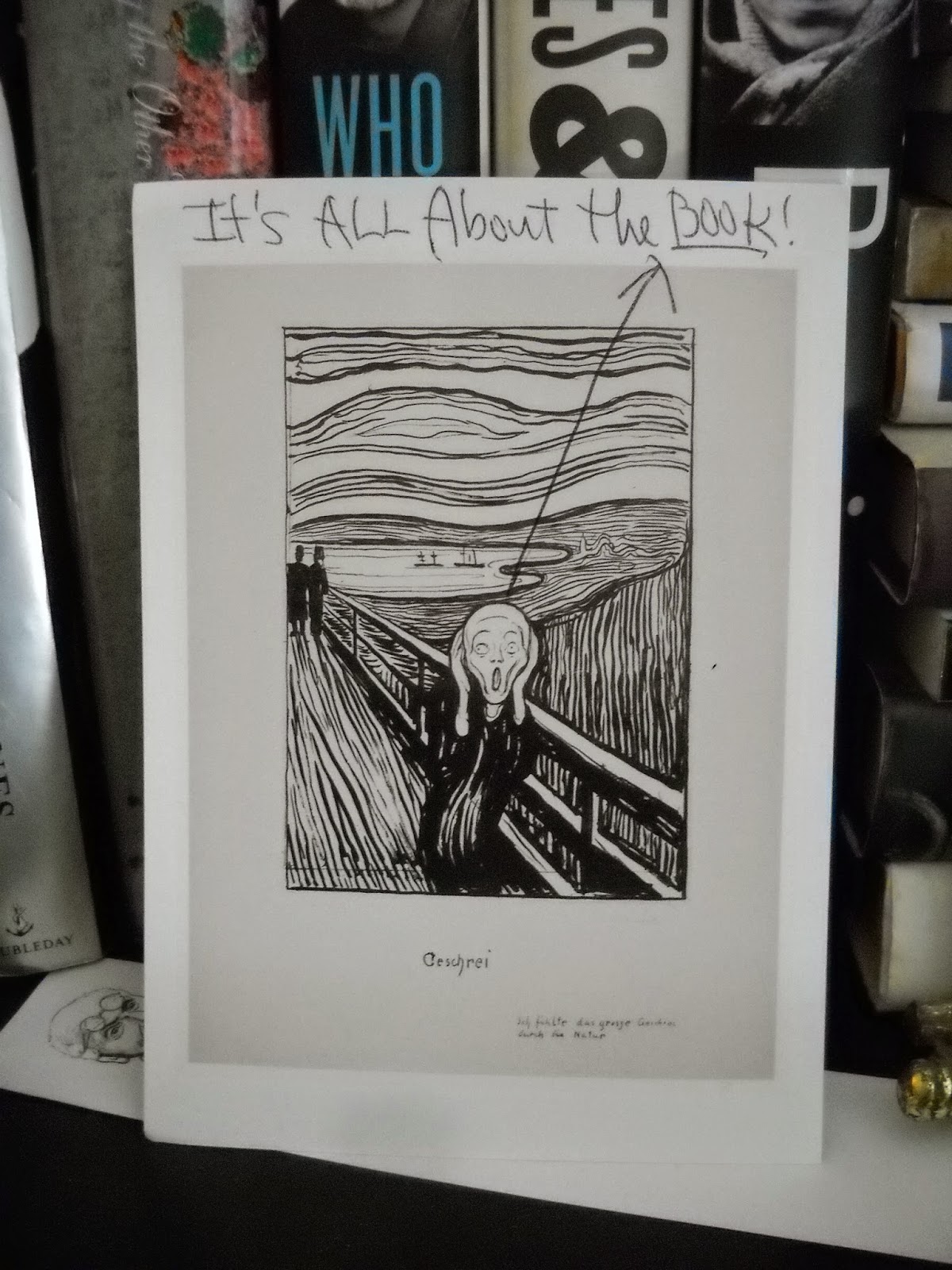

THANK YOU everyone who has contributed to my crowd funding campaign in the past

few weeks! I am seeking funds to help me pay a copy editor and graphic designer to complete my forthcoming book Freedom of Expression: Interviews With Women in Jazz.

The quote is a brief excerpt from my conversation with pianist

Connie Crothers, one of the 37 musicians that are interviewed in the book.

The campaign continues through September 30.

Thursday, September 25, 2014

Saturday, September 6, 2014

Friday, September 5, 2014

Rock and Roll

|

| Singer Beverly Kenney |

Here's another excerpt from the introduction to my forthcoming book Freedom of Expression: Interviews With Women in Jazz. The book includes Q&A interviews with 37 female jazz musicians of all ages and ethnic backgrounds and representing just about every style of jazz one can imagine.

Rock and Roll

I don’t care who knows it,

I hate rock and roll!

—Beverly Kenney, “I Hate Rock and Roll,”

In the post-war years, despite fewer opportunities to play due to the diminish¬ing popularity of big bands, many women, both instrumentalists and vocalists, continued to find work and push jazz into unexplored territory, often in small ensembles that placed a greater emphasis on soloing and group interplay. Pia¬nists Pat Moran, Lorraine Geller, Beryl Booker, the German émigré Jutta Hipp, and Toshiko Akiyoshi (who would form with husband and saxophonist Lew Tabackin the world-renowned big band, the Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra) are just some of the distinctive, post-war jazz musicians who were known, recorded, and appreciated in their time and still have dedicated followings today.

At the same time, rhythm and blues, alternately known as “rock and roll,” depending upon the skin color and gender of the person singing and playing, became the favored dance music of both black and white teenagers. As with jazz, the contributions by female musicians to the development of rock and roll are typically ignored in most historical narratives.

Although the advent of rock and roll is usually traced back to a handful of 1950s recordings by such iconic male artists as Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Bill Haley, and Elvis Presley, female artists, including Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Big Mama Thornton, and Ruth Brown, to name just a few, were just as crucial to the development of this new musical form that drew equally on blues, gospel, jazz, country, and Cajun music. Recordings such as Tharpe’s “Strange Things Happening Every Day,” Thornton’s “Hound Dog,” and Brown’s “Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean,” were as musically influential, if not more so, as Berry ’s “Maybeline” or Haley ’s “Rock Around the Clock.”

Less than a decade after the release of these recordings, the emergence of three British rock and roll bands, the Beatles, the Kinks, and the Rolling Stones, each one heavily indebted to the blues and roots of black American rock and roll, heralded another musical and cultural transformation. Many young British and American women, inspired by the music and fashion of the British beat movement, formed their own all-female bands, including New York’s Goldie and the Gingerbreads, Detroit’s Pleasure Seekers, and the Liverpool-based quartet the Liverbirds, of whom Beatles guitarist and singer John Lennon famously quipped: “Girls with guitars? That’ll never work!”

In 1963, one year before the Beatles made their American television debut, the publication of Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique ignited what we now recognize as the second wave of the women’s movement. Friedan, who would found and become the first president of the National Organization for Women (NOW), described the depression and anxiety many college-educated women were experiencing in their prescribed roles as mothers and housekeepers. But once again, change was in the air. Over the next two decades, the women’s movement would gain momentum and influence and inspire the work of a new generation of female musicians across all genres, including jazz.

I hate rock and roll!

—Beverly Kenney, “I Hate Rock and Roll,”

In the post-war years, despite fewer opportunities to play due to the diminish¬ing popularity of big bands, many women, both instrumentalists and vocalists, continued to find work and push jazz into unexplored territory, often in small ensembles that placed a greater emphasis on soloing and group interplay. Pia¬nists Pat Moran, Lorraine Geller, Beryl Booker, the German émigré Jutta Hipp, and Toshiko Akiyoshi (who would form with husband and saxophonist Lew Tabackin the world-renowned big band, the Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra) are just some of the distinctive, post-war jazz musicians who were known, recorded, and appreciated in their time and still have dedicated followings today.

At the same time, rhythm and blues, alternately known as “rock and roll,” depending upon the skin color and gender of the person singing and playing, became the favored dance music of both black and white teenagers. As with jazz, the contributions by female musicians to the development of rock and roll are typically ignored in most historical narratives.

Although the advent of rock and roll is usually traced back to a handful of 1950s recordings by such iconic male artists as Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Bill Haley, and Elvis Presley, female artists, including Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Big Mama Thornton, and Ruth Brown, to name just a few, were just as crucial to the development of this new musical form that drew equally on blues, gospel, jazz, country, and Cajun music. Recordings such as Tharpe’s “Strange Things Happening Every Day,” Thornton’s “Hound Dog,” and Brown’s “Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean,” were as musically influential, if not more so, as Berry ’s “Maybeline” or Haley ’s “Rock Around the Clock.”

Less than a decade after the release of these recordings, the emergence of three British rock and roll bands, the Beatles, the Kinks, and the Rolling Stones, each one heavily indebted to the blues and roots of black American rock and roll, heralded another musical and cultural transformation. Many young British and American women, inspired by the music and fashion of the British beat movement, formed their own all-female bands, including New York’s Goldie and the Gingerbreads, Detroit’s Pleasure Seekers, and the Liverpool-based quartet the Liverbirds, of whom Beatles guitarist and singer John Lennon famously quipped: “Girls with guitars? That’ll never work!”

In 1963, one year before the Beatles made their American television debut, the publication of Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique ignited what we now recognize as the second wave of the women’s movement. Friedan, who would found and become the first president of the National Organization for Women (NOW), described the depression and anxiety many college-educated women were experiencing in their prescribed roles as mothers and housekeepers. But once again, change was in the air. Over the next two decades, the women’s movement would gain momentum and influence and inspire the work of a new generation of female musicians across all genres, including jazz.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)