Pianist Connie Crothers, one of the giants of jazz, passed away

in the early hours of August 13, 2016 after a brave battle with cancer. She was 75. As one of jazz music's great virtuosos, Crothers was a bridge between strains

of seemingly disparate musical camps, especially so-called standard-tunes players and free

improvisers. Like her mentor pianist Lennie Tristano, her approach to free (or “spontaneous”)

improvisation was founded in a deep knowledge of and appreciation for the earliest practitioners of

jazz (e.g. Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge, Billie Holiday). But while she saw herself as part of a lineage, she considered

jazz to be an evolving art form, and believed the music was in fact “heading into

something incredible.”

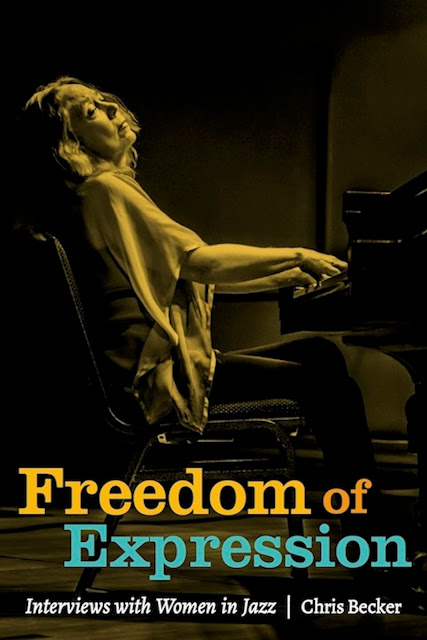

It is Crothers who graces the front cover of my book Freedom of Expression: Interviews With Women

In Jazz. (She is one of 37 musicians interviewed.) This powerful image of Crothers at the piano, all ten fingers on the

keys, her head tilted back, perfectly captures the feeling of transcendence that comes from

playing music, as well as the sacrifices necessary to achieve such a state of

grace. Not surprisingly, the image has resonated with many women, as it conveys the

struggles and triumphs uniquely experienced by women in jazz.

|

| Photo of Connie Crothers by Peter Gannushkin |

The cover’s gold, rose, and turquoise colors were inspired

by the stained glass windows of artist Henri Matisse’s Chapelle du Rosaire de

Vence. For many of us, music is our religion; dogma doesn’t work when your

craft requires you to be open and receptive to influences and inspiration from

the past and the present, and to play in response to what’s in your heart, not in your head. That's a pretty good description of the kind of

spontaneous and freely improvised music Crothers played so masterfully, both as

a soloist, and in collaboration with some of the great improvisers of our

time.

Crothers began studying classical (or “European”) piano at

age 9 and went on to major in composition at the University of California at

Berkeley. At Berkeley, her teachers emphasized “procedure and structure” and

“compositional rigor” over emotional expression, which didn’t sit well with

Crothers. She began listening to jazz, and upon hearing Tristano's recording “Requiem,” had a shamanistic vision that inspired her to leave school and travel to New

York to study and master a completely different musical language:

“ . . . during the length of the track ["Requiem"], I had an amazing

experience where I saw my future. . . . I knew nothing about New York City; I

knew nothing about improvising or about jazz, but I knew that that’s what was

going to happen. It was almost as if it had already happened.”

Tristano, who was blind, told Crothers singing along with

records was an important key to developing an ear for improvisation. In her own

teaching, Crothers emphasized the importance of learning and internalizing a tune's melody,

not its chords, in in order to improvise more freely and creatively:

“What I try to get to instead with [my students] is have them play

the strict melody of a tune with no ornamentation whatsoever. . . . like how

they would sing it, just very simply. And then, instead of trying to think

chords, just hear the melody, and let the melodic line get released . . . I

like to say the melody has everything in it. It has the harmonic sound, so

you’re getting the harmony from your ear, rather than thinking ‘C7’.”

For those of you scratching your head and wondering how this

concept is applied practically in a performance setting, it can be helpful to

understand free improvisation does not necessarily begin with common-practice

musical building blocks, such as chord progressions, Western European song forms, or

clearly stated time signatures. Bassist William Parker, who has described

Crothers at the piano as “a queen at her throne,” describes instead an alternate

“periphery” of sounds that musicians tap into when playing free. The resulting

sounds are limited only by a musician’s imagination and technique. (And Crothers' imagination and technique were formidable!) Crothers

believed playing free is one of the most challenging things for a musician to

attempt:

“. . . if you have that understanding of music, you’re never

going to be able to fake it. You can’t. You have to tap into that deep well of

understanding every time you express your music. . . . With no parameters to

guide you, it’s on you to create music that’s beautiful and has an inner logic.

I find this extremely intriguing and really exciting — thrilling in fact!”

This is music that is the opposite of walls, borders,

paranoia, prejudice, and hate. In fact, Crothers equated freedom with truth

plus beauty plus love, with love being an ever-present and wholly accessible source for musical and spiritual inspiration.

(Henry Grimes and Connie Crothers in performance, April 26, 2016.)

When Crothers and I first spoke, she told me how pleased she was to be asked to be included in a project that focused on and celebrated the contributions of women to jazz. She named several pioneering jazz women, including pianist and bandleader Lillian Hardin Armstrong, saxophonist Vi Redd, and guitarist Mary Osborne, who each made major contributions to the development of this music. For Crothers, New York in the years before the women’s movement was a place where men a generation ahead of her and her peers still thought women were inferior and not be taken seriously:

“When I first came to New York City in 1962 . . . when I

went to a club, it was like walking a gauntlet. It was just understood that if

there was a woman on the premises, the men were gonna hit on her. . . . A lot

of women in those days were kicked off of bandstands and out of the recording

dates because of the prevailing notion, which was very strong then, that men

were better, that women were not as good as men.”

I mention this to make it clear that Crothers was both an activist and a

feminist. She was also a strong advocate for independent artists. In 1982,

Crothers and drummer Max Roach co-founded the label New Artists Records when no

label expressed interested in releasing an album of their duets. New Artists Records would later become a cooperative, with each artist contributing to its

operating expenses and receiving 100 percent of their album sales. It is an

excellent place to sample and purchase some incredible recordings by Crothers,

including the aforementioned album of duets with Max Roach titled Swish and her epic live solo piano

recording Concert in Paris.

What remains to be seen is where a new generation of

musicians go with the music. Like Duke Ellington, Crothers was an optimist, and

she made her feelings about the future of jazz plain to me:

“For many years, the jazz world was sort of divided into

groups. . . . there was a kind of division between the free improvisers and the

jazz musicians who played tunes, as well as other divisions based on other

considerations. But now we’re moving into a new era. I feel that is already underway

. . . I call it a jazz renaissance.

“But the thing that I think has to happen . . . is that all

the groups need to open up and find out about each other, because there are so

many valuable musicians in each group. And if they find out about each other,

the art form will just blossom! I look forward to that. I hope to be a part of

that.”

And I’ll just leave it at that for now. Connie, we love you madly.

Thank you, Chris!!

ReplyDeleteYou bet, Jan. Thank YOU.

DeleteWonderful piece, Chris!

ReplyDeleteThank you.

Delete