Freedom of Expression: Interviews With Women in Jazz is a collection of inspiring and in-depth interviews with 37 women musicians of all ages, nationalities, and races and representing nearly every style of jazz one can imagine. The interviewees include

Carmen Lundy,

Dee Dee Bridgewater,

Eliane Elias,

Helen Sung,

Anat Cohen,

Diane Schuur,

Sherrie Maricle,

Sharel Cassity,

Brandee Younger,

Jane Ira Bloom and many other incredible artists. The 320-page book includes 42 photographs, and a 25-page introduction to the history of women in jazz.

Freedom of Expression: Interviews With Women in Jazz is available for purchase from

Amazon. Here in Houston, TX, you find the book at

Brazos Bookstore,

The Jung Center of Houston Bookstore, and

Casa Ramirez FOLKART Gallery.

What follows is an excerpt from the book: the introduction to and a portion of my interview with drummer, composer, and producer

Terri Lyne Carrington.

|

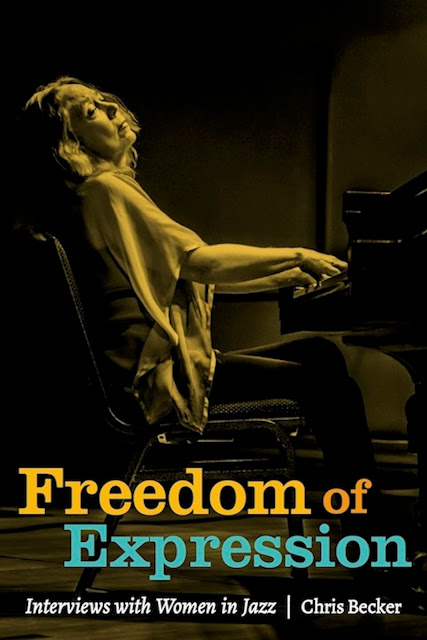

| Terri Lyne Carrington. Photo by Phil Farnsworth. |

Drummer, composer, and producer

Terri Lyne Carrington is one of the first musicians I interviewed for this book. In our conversation, she quotes composer Duke Ellington to help explain her relationship to jazz:

“I don’t doubt my connection with it, because I don’t look at it as a certain thing. It’s creative music. Duke Ellington said jazz means ‘freedom of expression.’ And I think that everything that I do, for the most part, feels like jazz. As far as creative music and freedom of expression, like Duke Ellington said, there’s no ‘box’ for that.”

Her reply provided me with the first three words to the title of this book. Her early participation as an interviewee also opened some doors for me as I contacted other musicians around the country about this project. There’s no question, Carrington commands a great deal of respect among the music community at large.

Born in 1965 in Medford, Massachusetts, Terri Lyne Carrington is part of a multi-generational musical family that includes her father, saxophonist Sonny Carrington, and grandfather, drummer Matt Carrington, who played with Fats Waller and Duke Ellington. Carrington was a child prodigy and began taking classes at Berklee College of Music under a full scholarship at the age of 11. In 1983, she moved to New York and became an in-demand musician, drumming for jazz luminaries Lester Bowie, James Moody, Pharoah Sanders and many others. Her extensive résumé includes television gigs as the house drummer for the Arsenio Hall Show and Quincy Jones’ late-night show Vibe, hosted by the comedian Sinbad. She has also toured extensively with pianist and composer Herbie Hancock.

In addition to being a virtuoso drummer, Carrington is a formidable producer, a role that allows her to bring together artists from all genres into her creative projects. I interviewed Carrington for this book not long after the release of her Grammy Award-winning album

The Mosaic Project, a collection of tracks performed by some of the world’s most highly respected female instrumentalists and singers, including Dee Dee Bridgewater, Carmen Lundy, Helen Sung, and Anat Cohen, who are also interviewed in this book. In the liner notes to

The Mosaic Project, Carrington says the album “comments on historical, current, and appropriately feminine themes,” and for listeners new to jazz, it is a wonderful, engaging, and profound introduction to this music.

When did you first begin studying music?

My grandfather was a drummer. He passed away before I was born. I guess my father was my first teacher.

At around age 9, I started taking private lessons at like a music shop. But I never, throughout my whole public-school time period, took music classes, except for violin, in third grade.

So at a young age, the drums were your main instrument?

It was always just the drums! I took piano lessons, but I guess I never really felt I was going to play the piano. I wanted to know music theory and things like that. But for the most part, it was just the drums.

At that age, before you were even a teenager, what kind of music were you listening to? And what kind of stuff were you playing on the drums?

Well, see my dad was a saxophone player too. I was into jazz because that was what he was into. But I was also listening to the popular music of the day because . . . I was young! [laughs] I had friends! So I listened to people in the jazz world, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Michael Jackson, and Earth Wind & Fire as well.

And your family, as things got more serious, they were 100 percent behind this career choice that was forming for you at such a young age?

Oh, yeah! Yes, they were always supportive. Still are. My dad still plays a little bit, and my success was one of three generations.

So maybe it wasn’t that unusual to have a musical prodigy in the house?

Well, not unusual for us! [laughs] I think you’re very fortunate when you have a family that understands it and doesn’t think music is something that should be a hobby. I wouldn’t be the musician I am today without my dad and all of his knowledge.

You began at Berklee at the age of 11? Is that correct?

Yes. I was taking private lessons and jamming with ensembles. I didn’t really attend real classes, mainly just private lessons on drums and piano.

Did you think back then, as a young woman, a young woman playing drums, you were cutting your path, doing something that had not necessarily been done before?

I think as a young person, no. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve been seeing myself more as a pioneer in a sense.

As a trained jazz musician, with a lot of experience playing live and tour¬ing, was the transition to playing on television weird?

No, because I always had respect for great artists in the R&B field and the pop field. And as a result of my television gigs, I ended up playing with a lot of those people, like James Brown, Whitney Houston, Rick James—all kinds of people. It was just fun for me. It wasn’t like I was playing down to that music or those artists at all!

Did you end up shifting your focus as a musician as a result of the schedule demands of television?

Yes, but I think your focus should shift every time you work in and play another style. It wasn’t about chops or anything like that. When I played jazz, which was a lot less during that time, I played better, because my approach was fresh. Because I had been away from it, I got better.

Was playing for Rick James different from playing for Herbie Hancock?

Yes. TV is a very different animal. You have to play in 30 seconds with such energy. It’s not about a building; it’s about getting to the point very quickly. When you’re coming in and out of commercials, you have to sound good from the moment you hit the first stroke and absolutely have to have a certain level of energy.

When I play certain styles of jazz, it’s more about telling a story, and starting something and building something into an experience for the listener.

But with TV shows, and maybe pop music in general, it’s a little different. It’s about really performing from that “one.” It’s entertainment. So, maybe it’s not as spontaneous. But I’m not saying it’s not creative; that music is creative too!